Jean Baudrillard: Postmodernism's Prophet?

We aren't living in a simulation, we have become a simulation

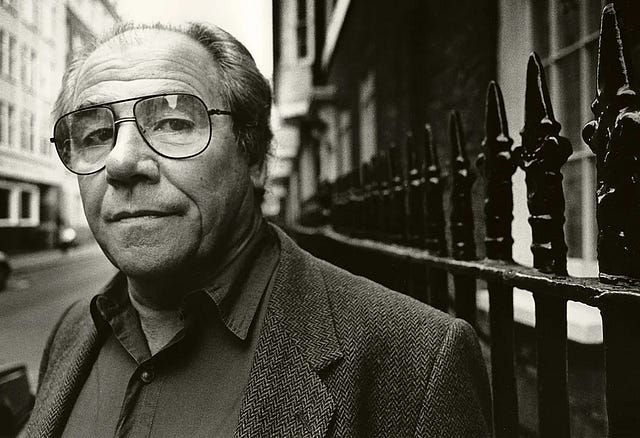

France was the hotbed of postmodernism from the 1960s through the 1980s, and one prominent postmodernist was Jean Baudrillard (1929–2007). His original thinking was several decades ahead of his time. Several of his ideas now seem like prophesies about our current social and technological crises.

Baudrillard (bo-dree-AR) could be classified more as a social critic than as a philosopher. He based his philosophy on the life of signs and how technology affects people and society. In three books, The System of Objects (1968), The Consumer Society (1970), and For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (1972), Baudrillard combined the philosophy of semiology with the critique of everyday life offered by French sociologist Henri Lefebvre (1901–1991).

Lefebvre (le-FEV), a Marxist, argued that capitalism had colonized everyday life and had turned it into a zone of consumption, pushing people to believe that they needed to relieve the boredom of everydayness through purchasing products or experiences. Lefebvre had also shown how space is a complex social construction based on social values, and he considered capitalism to be the dominant social value that produces social space.

Sign Value

Baudrillard thought that Lefebvre’s Marxist critique of life as everydayness had some merit but was insufficient and needed to be enhanced by a theory of signs — how words and symbols signify and represent meaning. Baudrillard accepted that signs are an integral part of society because they articulate social meanings and are organized into systems of meaning. He argued that commodities should be characterized not strictly through their use and exchange value, as Marx had said, but by their “sign-value”: what those objects signify and represent.

For example, the value of a luxury watch lies more in its sign-value as an expression of prestige, wealth, and style than in its “use-value” as a timekeeping device or its monetary exchange value. In everyday life, people purchase and display their commodities as much for their sign-value as for their use-value. This insight from Baudrillard is even more true now, decades later, as consumerism is increasingly dominated by the sign-values of brand loyalty and the need to be “on trend.” Look around you to see how many people are wearing clothing emblazoned with a brand name, having paid for it many times the actual use-value of the clothing.

Presaging developments in electronic media in the early 2000s are Baudrillard’s notions of the “simulacra” and the “real.” He sees as fundamental to the rupture between modernity and postmodernity that modern societies are organized around commodities but that postmodern societies are organized around simulation and play. He laid out in his 1981 book, Simulation and Simulacra, that we are now ruled by simulation. Understand that he was not thinking about computer simulation but the social reproduction of signs and. Baudrillard argued that identities and meanings are constructed by the appropriation of cultural signs — images, codes, and models — that determine how we view ourselves; how others view us; and, therefore, how we relate to each other.

The Force of Simulation

Baudrillard broke with the Marxist grand narrative that social class differentiated boundaries between people. That was true in modernity, but in the postmodern world, differentiation by class, gender, politics, economics, culture, and sexuality are imploding under the force of simulation. Baudrillard claimed that people have so much access to signs, which are exchanged so freely, that differences between groups collapse amid the dissolving social boundaries and structures on which society is built and on which social theory is focused.

Electronic media and digital technologies propel this transformation. They deliver a constant stream of signs and references to viewers without any consequences to them. For example, the top grossing film in 1980, the year Baudrillard was developing his theory, was The Empire Strikes Back. Millions watched the film, but none of it was real. The death and destruction on-screen had no consequences for the viewers, yet the images and signs of the film excited people into a state of what Baudrillard called “hyperreality,” in which entertainment provides experiences more intense and involving than the realities of everyday life. We see how common it is for people to identify themselves by their fandoms of television shows or music artists. From amusement parks, to shopping malls, to television shows, to video games, to social media, the images, codes, and models of hyperreality are more real to people than real life is. Real life is a desert compared to the fantasylands offered by simulation.

The postmodern person is awash in simulacra. Baudrillard defines the simulacrum as the truth that conceals that there is no truth; the simulacrum is true. Human society has always had signs that mediated reality for us — that’s what words have always been. Now in the postmodern world, society has replaced reality with signs, and our human experience is a simulation composed of simulacra.

“From now on,” Baudrillard wrote, “signs are exchanged against each other rather than against the real.” Our life now is a procession of simulacra — all of culture’s images, codes, and models that construct our perceived reality — and our society is so saturated with simulacra that meaning is infinitely mutable to the point that meaning is now meaningless.

What Baudrillard Was Actually Talking About

Pause to understand something important here. As I write this in 2025, people debate the effects of artificial intelligence, virtual reality, computer simulations, the so-called metaverse, and deepfake videos. These are not what Baudrillard was talking about 40 years ago. He’s talking about the broader cultural forces of which these new simulation technologies are simply expressions.

The technology of virtual reality is an extension of television and films, which immerse viewers in simulacra. Television at best shows us copies of reality. Watching television, we don’t see the US president giving a speech; we see an image of that person. That’s not in itself problematic, but when the copy on screen is unfaithful to the underlying reality, it obscures what’s real. The image before us is what’s real for us because the image is what we experience. If the image is fictional, maybe a TV drama about a real US president that has an actor pretending to be that person, it is a copy divergent from an original, even though it pretends to be a faithful copy.

Then there’s the pure simulacrum — perhaps a TV show about an entirely fictional president. In these images, signs reflect other signs without any claim to reality. The simulacra of the president are what is real and become more familiar and real to viewers than the actual president. Sounds far-fetched? Well, a 2015 opinion poll found that the fictional president of the TV show, “The West Wing,” had a higher favorability rating than the actual US president, Barack Obama.

Baudrillard’s notion of the simulacra isn’t just limited to the realm of entertainment. Their more pernicious appearances are in advertising and political propaganda. We are besieged by advertising, and Baudrillard is dead on in describing it as simulacra that at best pretend to be real but more often present a completely manufactured set of signs that is connected only to other signs. Advertising sells a fake world, a hyperreality in which everything is better than everyday life; all you have to do is purchase what the simulacra are selling and your life will be as happy as the simulacra people in the commercial.

Political propaganda similarly provides signs that are conjured up to seem to be connected with reality but are engineered to deceive. Today, some people talk about us living in a “post-truth” society, and that politics and society is losing touch with what it true and real. But back in the 1980s, Baudrillard observed that simulacra have always existed. What differs now, he claims, is that there is only the simulation, only copies of copies, and originality is a meaningless concept in our society. Just look at how social media is ruled by the meme. Look at music and visual media and how its products are mostly copies of copies.

Was Baudrillard a Prophet?

On the one hand, it is almost eerie how Baudrillard’s ideas seem much more true now than when he proposed them. Baudrillard mentions the “ecstasy of communication,” a state in which a person has close instantaneous access to a plethora of information and images. In this state of ecstasy, a person becomes a pure screen. The person is pure absorption, a surface on which is shown an overexposed, transparent world of simulacra. Baudrillard expressed these thoughts before the Internet, before smartphones, before advanced video games. Now, untold number of people are mere screens onto which tech corporations feed simulacra.

On the other hand, it is easy to criticize two of Baudrillard’s claims. The first is that postmodernity would result in differentiation imploding is partly naive. He was correct that electronic media and digital technologies have brought about much easier sharing of cultural and intellectual ideas. Concepts of cultural identity and gender are more fluid than ever, but differentiation of categories of class and race are still sharply drawn. True, technology has changed the nature of society and communication, but has it changed human nature and tendencies?

Baudrillard also seemed to not foresee how hyperreality could affect real-life. In Ukraine, a TV show about a fictional president was so popular, that when the actor playing that president ran for election, he won, becoming President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. No one could say, though, that he is not a real president conducting real actions. Then there’s Donald Trump, a blend of TV personality and real-world business tycoon turned political boss.

As a big fan of Umberto Eco and Guy Debord, Baudrillard has a soft spot in my heart and mind. I feel they all attempted to warn us of how we were breaking from reality. One example that always comes to my mind is Las Vegas. I feel under all the layers of signs and simulacra it will take a significant upheaval to get back to reality - difficult but not impossible. Thank you for writing this ❤️

Great analysis. I just did a couple of posts quoting Baudrillard in relation to an ecotourism centre which, to attract visitors, used my photographs of butterflies which had been wiped out in the construction of the ecotourism centre.